The Biased Brain: The Science of Making Smarter Decisions

Think back to the last time you made a decision you regretted.

Maybe it was an expensive gadget you bought on impulse, only to have it gather dust a week later. Perhaps it was hiring a candidate who charmed you in the interview but proved to be a poor fit for the team. Or maybe it was stubbornly sticking with a failing project, pouring good money after bad, long after you should have cut your losses.

In the quiet aftermath, a frustrating question often surfaces: “What was I thinking?”

You’re a smart person. You’re rational. Yet, you still make irrational choices. The comforting and slightly unsettling answer is that this is perfectly normal. Our brains, for all their marvels, are not perfectly logical computers. They are running on ancient software, full of bugs, shortcuts, and biases that served our ancestors well on the savanna but often lead us astray in the modern world.

The journey to making better decisions, then, isn’t about becoming "smarter." It's about becoming an aware operator of your own mind—learning to spot the bugs in your thinking and knowing when to deploy the right mental software for the job.

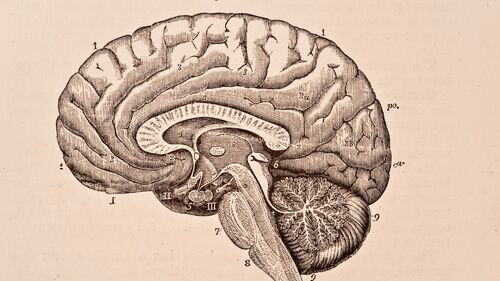

Meet Your Two Brains

The first step is to understand the fundamental conflict happening in your head. As Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman explains, we have two distinct systems of thought constantly at work.

This masterpiece introduces us to "System 1" and "System 2." System 1 is our fast, intuitive, emotional, and automatic pilot. It’s what helps you instantly know that 2+2=4 or read the mood of a room. System 2 is our slow, deliberate, logical, and effortful thinker. It’s the one you engage when solving a complex math problem or parking a car in a tight space. Most of our decision-making errors occur when we rely on the impulsive System 1 to do a job that requires the careful deliberation of System 2.

Unmasking the Bugs

Your fast-thinking System 1 is not only lazy, but it's also highly susceptible to manipulation and flawed assumptions.

For instance, its desire to fit in makes it vulnerable to external influence. We often agree to things not because they are logical, but because of deep-seated psychological triggers.

This classic book unmasks the six universal principles of persuasion—like Reciprocity, Social Proof, and Scarcity—that others can use to "hack" our System 1 and get us to say "yes" without our conscious consent.

Furthermore, our brains are terrible at understanding randomness and extreme events. We are wired to see patterns and create simple stories, which makes us blind to the impact of the highly improbable.

Nassim Taleb’s concept of the "Black Swan" event teaches us that the most consequential things in life are often the ones we could never have predicted. Relying solely on past experience in a world full of black swans is a recipe for disaster.

The Antivirus Toolkit

So, our brains are buggy. What can we do about it? The good news is, we can install some powerful "antivirus" software—a set of mental frameworks to counteract our innate biases.

Tool #1: Think in Bets, Not Certainties.

We often judge our decisions based on the outcome. If it worked out, it was a good decision; if it didn't, it was a bad one. This is a trap. A great process can lead to a bad outcome, and vice versa. The key is to embrace uncertainty.

Written by a former world champion poker player, this book teaches us to think like a gambler: to see the world in probabilities, not absolutes, and to separate the quality of our decision from the quality of the result.

Tool #2: Build a Latticework of Mental Models.

As the saying goes, "to a man with only a hammer, every problem looks like a nail." Relying on a single way of thinking is dangerous. The solution is to collect and use models from a wide range of disciplines.

Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett's legendary partner, advocates for building a "latticework of mental models." By understanding core concepts from physics, biology, psychology, and economics, you can analyze a problem from multiple angles and arrive at a more robust conclusion.

Tool #3: Be a Choice Architect, Not a Victim.

Since our brains are easily led astray, why not use that to our advantage? We can consciously design our environment and choices to make the better option the easier option.

This book introduces the concept of a "nudge"—a small change in how choices are presented that can dramatically alter behavior without restricting freedom. Whether it's putting healthy food at eye level or setting up automatic savings, you can architect your life for success.

Tool #4: Cultivate the Mindset of a "Superforecaster."

Finally, making good decisions is a skill that improves with practice. But what does that practice look like? It involves cultivating a specific set of intellectual habits.

By studying individuals who are exceptionally good at predicting future events, this book identifies their common traits: they are intellectually humble, open to new evidence, comfortable with numbers, and constantly updating their beliefs. They see forecasting not as a gift, but as a practice.

The journey from a reactive decision-maker to a wise one is not about achieving intellectual perfection. It's about moving from being a victim of your brain's programming to being its aware operator. It's about cultivating the humility to question your own intuition, the curiosity to seek out different perspectives, and the discipline to follow a better process.

Start today. In your next decision, no matter how small, simply pause and ask yourself: "Is this my fast brain or my slow brain talking?" That single question is the first, most powerful step.